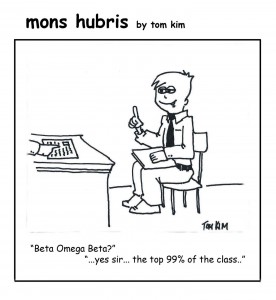

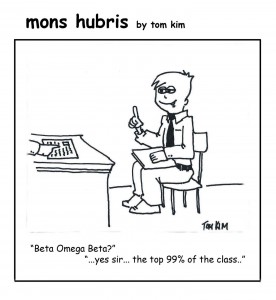

Reflecting on my first year of teaching and advising, I often find myself thinking about the Hubris-Humility Index.

Reflecting on my first year of teaching and advising, I often find myself thinking about the Hubris-Humility Index.

The Hubris-Humility Index is a concept invented by political scientists John Mearsheimer (Chicago; full disclosure, he was my dissertation committee chair) and Stephen Van Evera (MIT) in order to (according to Mearsheimer here) “measure the amount of hubris and humility packed into any individual.”

To get a high score on the hubris-humility index, which is desirable, it is essential to have large quotients of both hubris and humility. If an individual has an abundance of one quality, but a shortage of the other, then he or she gets a low score. A lot of hubris cannot compensate for a lack of humility, and vice versa. In short, you need hubris and humility if you are to be a first-rate thinker.

The more I interact with students, the more I think the HHI is a really good indicator. A good portion of students ranks highly on the hubris side but is made up of terrible listeners who do not take any advice seriously. Then there is another large group of students who rank high on humility, are always ready to change their project and adapt it to your input, but lack the hubris to believe in their ideas and push them just a little bit harder. And in between there’s a small minority of, I’d say, at most 20% of the students, who do well on the HHI: they are bold enough to push their ideas and believe in them deeply, while at the same time being good listeners and putting in the time and effort to incorporate criticism in a thoughtful way that does not erase every trace of their own initial hunch. According to Mearsheimer and Van Evera, it’s this last group that will do well. I think they’re right. But two interesting questions emerge:

First, why is this so? I think the HHI is a good predictor of intellectual potential because to produce good work one needs two things: (i) to believe in it enough to get out of bed with a spring in one’s step and spend the necessary long hours at it and (ii) to be able to think carefully through every criticism (imagined or offered by others) one is fortunate to encounter. The problem is these two requirements often are at odds with each other. People who get very excited about their work often are poor listeners; and people who are great at incorporating criticism often feel they lost their own voice and lose interest in the project. The HHI captures one’s ability to have both these crucial features at once.

Second, can one improve one’s HHI score? Sure. I see it happening in two ways.

The first case is that of the graduate or visiting student (typically coming from an educational system somewhere in Asia or continental Europe, where creative thinking is not encouraged but discipline and obedience is key) who arrives scoring high on the humility factor but almost completely devoid of hubris. Over time, with perseverance, the right environment, and (I’d like to think) the right encouragement from advisors, these students often flourish into creative thinkers — while banking on the ability to listen and work rigorously through criticism that has been drilled into them for years.

The second case is that of the graduate or visiting student (typically from the U.S. educational system where creative thinking is relatively more encouraged but everyone is told they’re special) who arrives setting new records on the hubris score but has no idea what humility means. Over time, some of these students acquire the ability to listen and think through criticism in a way that is divested of emotional attachment, and eventually improve their humility score, achieving a high HHI.

By the way, thinking one’s special, or especially important, which is detrimental to scoring high on the humility factor, is clearly on the rise in the United States. NY Times columnist David Brooks’s favorite piece of sociological data:

In 1950, thousands of teenagers were asked if they considered themselves an “important person.” Twelve percent said yes. In the late 1980s, another few thousand were asked. This time, 80 percent of girls and 77 percent of boys said yes.

But how would you fare on the Hubris Humility Index?

Here’s an analogy I thought of today: classes are like dining rooms; workshops are like kitchens. During classes, particularly seminars — as in restaurant dining rooms — you get a chance to develop your taste, figure out what you like and what you don’t, and expose yourself to different ways of cooking / writing. In a workshop setting — as in a kitchen — you get a chance to try out and develop the skills that will enable you to cook / write what you like. That’s why it is so important for graduate students — and undergrads with intellectual aspirations — to move as fast as possible into a workshop setting, first as attendants (and sharp questioners), then as discussants, and finally as presenters. Classes don’t get you there; you don’t get exposed to the process of producing scholarship, only its product.

Here’s an analogy I thought of today: classes are like dining rooms; workshops are like kitchens. During classes, particularly seminars — as in restaurant dining rooms — you get a chance to develop your taste, figure out what you like and what you don’t, and expose yourself to different ways of cooking / writing. In a workshop setting — as in a kitchen — you get a chance to try out and develop the skills that will enable you to cook / write what you like. That’s why it is so important for graduate students — and undergrads with intellectual aspirations — to move as fast as possible into a workshop setting, first as attendants (and sharp questioners), then as discussants, and finally as presenters. Classes don’t get you there; you don’t get exposed to the process of producing scholarship, only its product. After a week of traveling and fighting a cold — which meant virtually zero blogging — I’m back.

After a week of traveling and fighting a cold — which meant virtually zero blogging — I’m back.  Each of these captures an essential part of the research process. The first one points at an inescapable tension, that between utility and complexity. A simple argument often has a certain “falsity” to it, as it leaves out important parts of the world. Simple arguments are powerful but often blunt. A complex argument, though perhaps it captures the world in more realistic and nuanced ways, is often useless. Complex arguments often have so many moving parts they lose generalizability. Aiming at a compromise between the opposite pulls of simplicity and complexity is central to writing a successful piece of scholarship — be it a term paper or a doctoral dissertation. My approach is to start with something simple and then let the process develop like an accordion in action: expand it to capture the complexity and nuance of the world, thus challenging the initial intuition, then compress it again, discarding the accessory and refocusing on the core of the argument, then expand it again, and so on and so forth.

Each of these captures an essential part of the research process. The first one points at an inescapable tension, that between utility and complexity. A simple argument often has a certain “falsity” to it, as it leaves out important parts of the world. Simple arguments are powerful but often blunt. A complex argument, though perhaps it captures the world in more realistic and nuanced ways, is often useless. Complex arguments often have so many moving parts they lose generalizability. Aiming at a compromise between the opposite pulls of simplicity and complexity is central to writing a successful piece of scholarship — be it a term paper or a doctoral dissertation. My approach is to start with something simple and then let the process develop like an accordion in action: expand it to capture the complexity and nuance of the world, thus challenging the initial intuition, then compress it again, discarding the accessory and refocusing on the core of the argument, then expand it again, and so on and so forth.  Reflecting on my first year of teaching and advising, I often find myself thinking about the Hubris-Humility Index.

Reflecting on my first year of teaching and advising, I often find myself thinking about the Hubris-Humility Index.